By guest blogger Jay Blossom

Hurricane Ian cut a catastrophic path across Florida on September 28, 2022, causing at least 109 deaths and resulting in perhaps $47 billion in damage. But before its landfall near Fort Myers, the storm had also landed on Cuba, and it had already hit one of America’s most remote and pristine national parks.

Just one day before, on September 27, 2022, Ian passed directly over Dry Tortugas National Park, a cluster of seven islands located 68 miles west of Key West, Florida. The combined area of all seven islands is between 100 and 150 acres, but 99 percent of the park’s area is the protected ocean surrounding these islands, with extensive coral reefs that support seabirds and undersea wildlife.

In the midst of this tropical wonderland rises Fort Jefferson, surely one of the most remarkable structures within the National Park System. Constructed entirely of brick brought in by ship from Pensacola, the fort was begun in 1846, with construction continuing for 31 years before the Army abandoned the effort, still unfinished, in 1874. With 16 million bricks, and covering 16 acres, Fort Jefferson is the largest brick structure in the New World.

I had the pleasure of visiting the fort on November 5, 2020, during a visit to the Florida Keys. The Yankee Freedom, an authorized concessioner of the National Park Service, offers a daily catamaran trip from Key West to Fort Jefferson. As the fort came into view, visitors like me had to wonder why the Army built a vast fort on a remote island at such great expense. What were they trying to protect? Whom were they trying to intimidate? Was it worth the cost?

The answer, in part, is pirates.

After Spain sold Florida to the United States in 1820, coastal trade rapidly increased between the Atlantic Seaboard of the United States and New Orleans, the port near the mouth of Mississippi. And ships traveling that route were prevented from hugging the south coast of Florida by the Keys, a coral archipelago that extends 180 miles in a gentle arc into the Gulf of Mexico. En route from the U.S. East Coast to New Orleans, sailors stopped at the Dry Tortugas, the last of these Florida Keys. Spanish map-makers had even given these islets a name that indicated that food could be found there — tortugas means “turtles,” and green and loggerhead turtles still use the islands as a nesting place. (Unfortunately, there is no fresh water to be found, which is why later British cartographers added the adjective “dry” to Spanish maps.)

Challenges for 19th-century sailors along this route included tropical storms, invisible coral reefs, a lack of fresh water, and piracy.

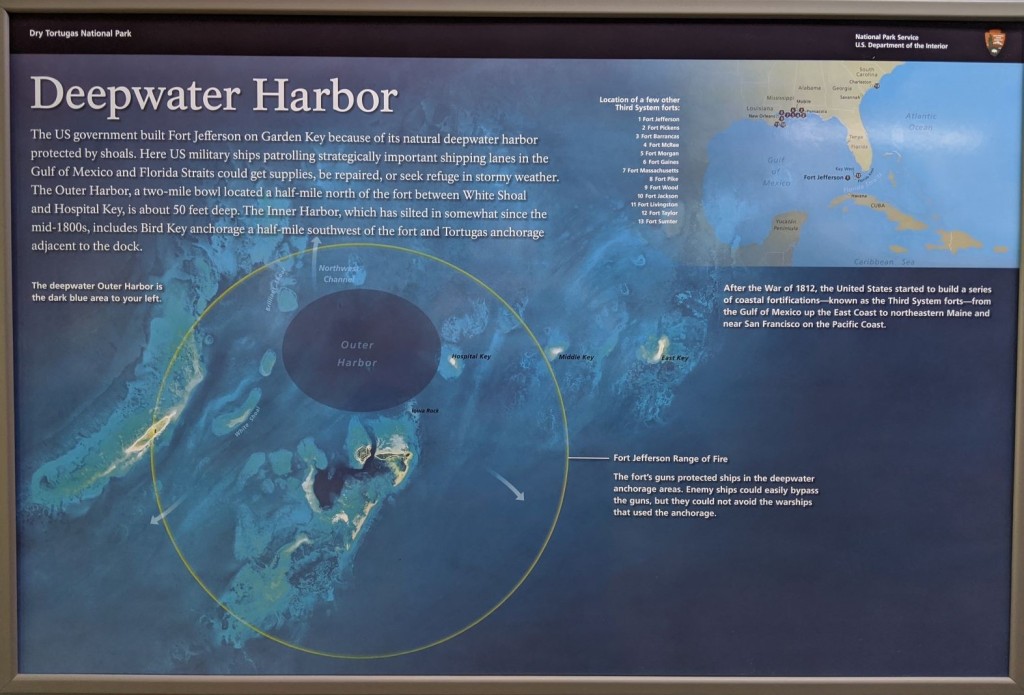

In 1825 and 1826 a lighthouse was constructed on one of the Tortugas to aid in navigation. A few years later, in 1829, the survey ship Florida stopped in the islands and later reported that they offered a protected harbor that, if occupied by a hostile foreign power, would put U.S. shipping in deadly peril. On the other hand, if the U.S. military preemptively fortified the islands, U.S. commercial vessels would be protected, both from piracy and from even bigger potential problems like the Spanish navy.

In 1845, the Tortugas finally became a national military reservation, and construction of the fort, which would occupy almost the entirety of one of the seven islands, began the following year. Plans for the fort included a 13-acre parade ground surrounded by a hexagonal curtain wall with corner bastions.

Perhaps the most interesting part of my tour of Fort Jefferson was hearing about the great privations that both the construction crews and the soldiers endured during the 30 years that the fort was being built by both enslaved and free laborers. Water was always in short supply — even with innovative steam-powered condensers that provided up to 7,000 gallons of desalinated water per day. Disease was rampant, death was common.

During the Civil War, the United States occupied Fort Jefferson to prevent it from falling to the Confederacy, and the fort became a prisoner of war camp. By late 1864, 583 soldiers and 882 prisoners lived there. But the following year, Fort Jefferson’s most infamous convicts arrived: Samuel Mudd, Edman Spangler, Samuel Arnold and Michael O’Laughlen, convicted co-conspirators in the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Mudd, the doctor who treated John Wilkes Booth’s broken leg, attempted and failed to escape on a departing ship in September 1865. Two years later, after the prison’s regular doctor died during a yellow fever outbreak, Mudd took over the medical care at the fort. As a reward for his service during the crisis, he was assigned to a desk job at the fort until he was pardoned by President Andrew Johnson in March 1869.

Twenty years later, the Army abandoned the fort altogether, and it became a quarantine station and then a coaling station before being reactivated during the Spanish-American War. After 1906, the fort was once again abandoned until President Franklin Roosevelt declared it a national monument in 1935. In 1992, Dry Tortugas National Park was established.

Today the fort is inhabited by a few employees of the park service. One woman staffed the gift shop on the day I visited; she said that because of recent bad weather, she hadn’t any internet or cellular service for days and didn’t even know that our boat was going to be arriving that morning. Our ship provided a guide for the history of the fort, as well as snorkeling equipment for those who wanted to explore the reefs surrounding the island. We used the toilets on the ship and also ate lunch on board, or we took sack lunches out to one of the picnic tables near the fort’s entrance. There are no services provided at the fort itself.

On the way back to Key West, my fellow passengers and I discussed whether we could actually see ourselves living in this remote paradise, 70 miles by water from the nearest car, house, or store. Most said no.

Aerial photographs taken in the days after Hurricane Ian’s landfall indicate damage to Fort Jefferson’s piers and damage to vegetation within the parade ground, with extensive flooding. Predictably, the storm also altered the sandbars that surround the islands and uprooted trees everywhere. Seaplane charters from Key West are once again being allowed to land, but as of October 6, 2022, the Yankee Freedom had not yet resumed its trips.

Great article about this special place. Visited 5 years ago and went snorkeling there. Beautiful spot with an interesting history. I hope they will be able to recover from the damage.